Beyond Bars: New Approaches To Prison Labor Reform

| By Breanna Conner |

Should prisoners be forced into labor during their sentence?

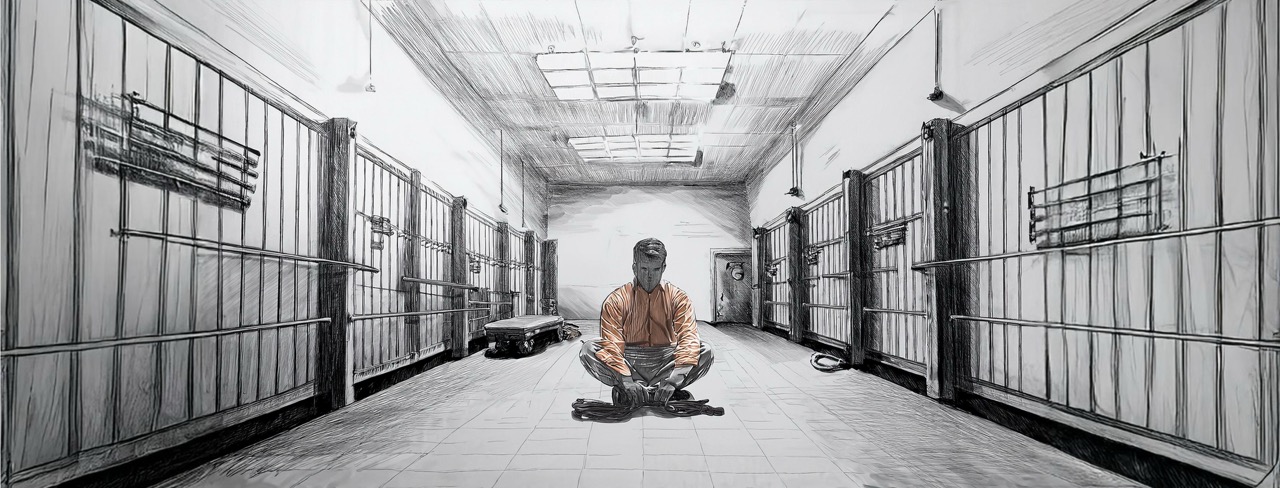

Prisons worldwide serve to confine and rehabilitate criminals throughout their sentences. Each jurisdiction utilizes diverse strategies to promote rehabilitation, enabling individuals to develop positive characteristics for successful reintegration into society upon release. However, the practice of prisoner labor and its potential infringement upon human rights has been a subject of ongoing debate. The 13th Amendment of the US Constitution, which prohibits slavery and involuntary servitude, contains an exception clause: “except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.” This constitutional provision has led to varied interpretations and implementations of prison labor systems across different states, sparking discussions about the fairness and effectiveness of such practices.

Rehabilitation and Revenue: The Impacts of Prison Work Programs

One argument in favor of penal punishment in the United States is that it helps rehabilitate prisoners by giving them a renewed sense of purpose. Rather than being idle, prisoners can restore their “human dignity (which) is linked to personal identity” and reconnect with the meaning of life through work (Gibson-Light, 2020, p.199). On average, two-thirds of prisoners engage in penal labor, which includes construction, textiles, maintenance, call centers, and even fighting fires (Gibson-Light, 2020, p.201). The worksites enable prisoners to adjust to new rules and restrictions that mirror life outside of prison. Additionally, their labor generates millions of dollars in profits for the state, which can be reinvested into the public sector. Furthermore, it allows for the production of goods and provision of services that might otherwise be unaffordable for local governments.

Penal Labor and the Poverty-Prisoner Cycle

However, penal labor often comes with significant drawbacks. Financial compensation is frequently inequitable, with some prison jobs paying as little as $0.20 per hour. This paltry wage makes prisoners feel as though their job is merely a “prison within a prison” (Gibson-Light, 2020, p.203). It’s crucial to note that prisons disproportionately incarcerate individuals from minority backgrounds. Consequently, these low wages trap their families in a cycle of poverty, potentially driving them to desperate measures to obtain necessities. This economic hardship can contribute to recidivism and create a pattern of generational imprisonment.

“Everyone has the right to work, to free choice of employment, to just and favourable conditions of work and to protection against unemployment.”

Article 23, United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Prop 6: Balancing Rehabilitation and Prisoner Rights in California

In the upcoming 2024 American elections, the state of California, one of sixteen states that allow involuntary servitude, will address the issue through Proposition 6, which aims to amend the state constitution to declare that “slavery and involuntary servitude are prohibited.” This proposed change reflects a growing recognition of the complex relationship between incarceration, labor practices, and human rights within the criminal justice system. This evolving awareness is exemplified by the experiences of incarcerated individuals themselves. One former inmate stated that while prison rehabilitation positively impacted his life, forced labor hindered his ability to enhance his education and participate in other rehabilitative activities.

Florida’s Controversial In2Work Program: Unpaid Labor in Prisons

Similarly, in the state of Florida, much of the functionality of prisons relies heavily on uncompensated prison labor. The private prison food provider Aramark operates the In2Work program, an unpaid labor initiative where incarcerated individuals prepare premium meals that their families can purchase. While the Florida Department of Corrections claims this program offers vocational training and reduces idleness among inmates, critics argue it exploits prisoners who receive no compensation for their work.

The Guardian reports on the experiences of Julius Smith, who has worked various jobs in prison without pay, and the case of Cheryl Weimar, who was allegedly beaten by correctional officers for refusing to work. These incidents highlight the controversial nature of unpaid prison labor programs. Despite ongoing efforts to reform the prison labor system at both the state and federal levels, meaningful changes have yet to be implemented, allowing programs like In2Work to continue operating in numerous Florida correctional facilities. This situation underscores the complex and often problematic intersection of private enterprise and the penal system in the United States.

Reimagining Rehabilitation: A New Approach to Prison Work

It is a fundamental human right to engage in dignified and consensual labor, regardless of one’s status as a prisoner. Prison systems that enforce penal punishment through forced labor are in direct violation of these rights, even if certain liberties are necessarily restricted as a consequence of conviction. A potential solution lies in implementing a system where prisoners can voluntarily choose to participate in labor, receiving a wage sufficient to afford in-prison amenities and food without placing undue financial burdens on their families. However, this wage should be carefully calibrated to prevent excessive monetary gains that could disrupt the prison environment or undermine the punitive aspects of incarceration.

Ultimately, the central question remains: How can we enable prisoners to make meaningful contributions to society while preserving the integrity of their sentence, all within a framework that respects their humanity? Striking this delicate balance requires a thoughtful approach that prioritizes rehabilitation, dignity, and public safety in equal measure. By addressing these complex issues head-on, we can work towards creating a more just and effective penal system for all involved.

The illustrations in this article were created using an AI image generator. All illustrations are ©Intelliwings.

Citations

Gibson-Light, M. (2020). Sandpiles of dignity: Labor status and boundary-making in the contemporary American prison. RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 6(1), 198-216.

Katsuyama, J. (2024). “Prop 6 Aims to Ban Forced Prison Labor in California.” KTVU FOX 2 San Francisco, KTVU FOX 2, , www.ktvu.com/election/prop-6-aims-ban-forced-prison-labor-california.

Sainato, M. (2024) “‘Florida Loves Prison Labor’: Why Most Incarcerated People Still Work for Free in the Sunshine State.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, www.theguardian.com/us-news/article/2024/jun/21/florida-unpaid-prison-labor.

“Universal Declaration of Human Rights.” United Nations, United Nations, www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights#:~:text=Article%2023,and%20to%20protection%20against%20unemployment. Accessed 30 Oct. 2024.